Debunking "We All Begin Female" | Paradox Proofs

Learn why the common "we all begin female" claim is wrong and what the science says.

“All humans begin as female in the womb.” It’s one of the most common biology myths today—from old science papers to blockbuster movies like Jurassic Park. The argument claims that because early embryos share the same initial structures, those structures must be female—so everyone begins female.

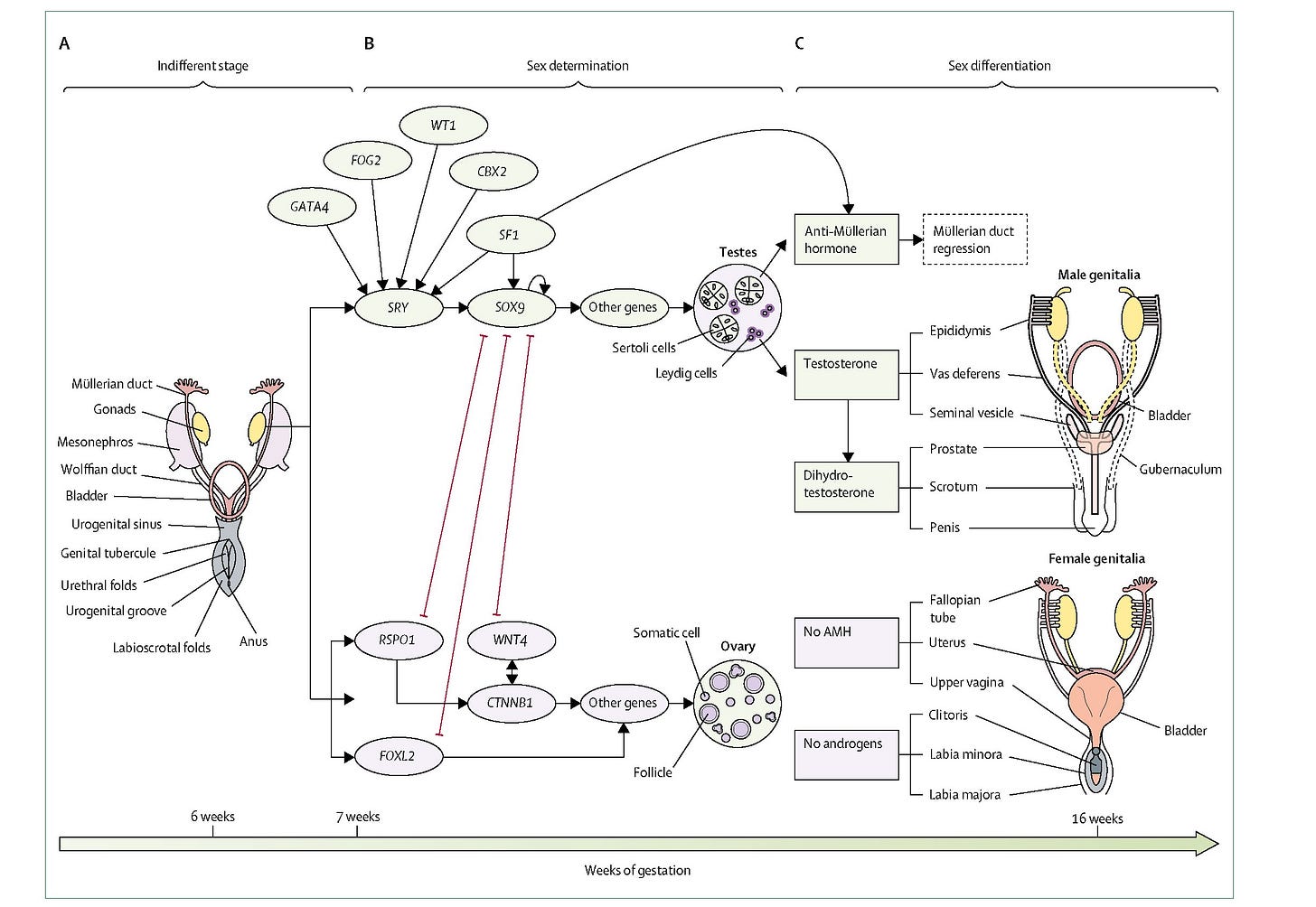

But those early structures aren’t female anatomy—they’re undifferentiated. Female development is not undifferentiated, nor is it “absence of male”; it is a specialized pathway guided by genetics, just like male development. For example, genes like WNT4, RSPO1, and FOXL2 actively promote ovary development—and when any of them are lost, testes can form instead; WNT and HOX networks actively build the Müllerian ducts, which become female internal genitalia; and COUP-TFII eliminates the Wolffian ducts, which would otherwise form the internal male genitalia. Therefore, female development is not a passive default; it requires active signals that drive the female pathway and block the male path.

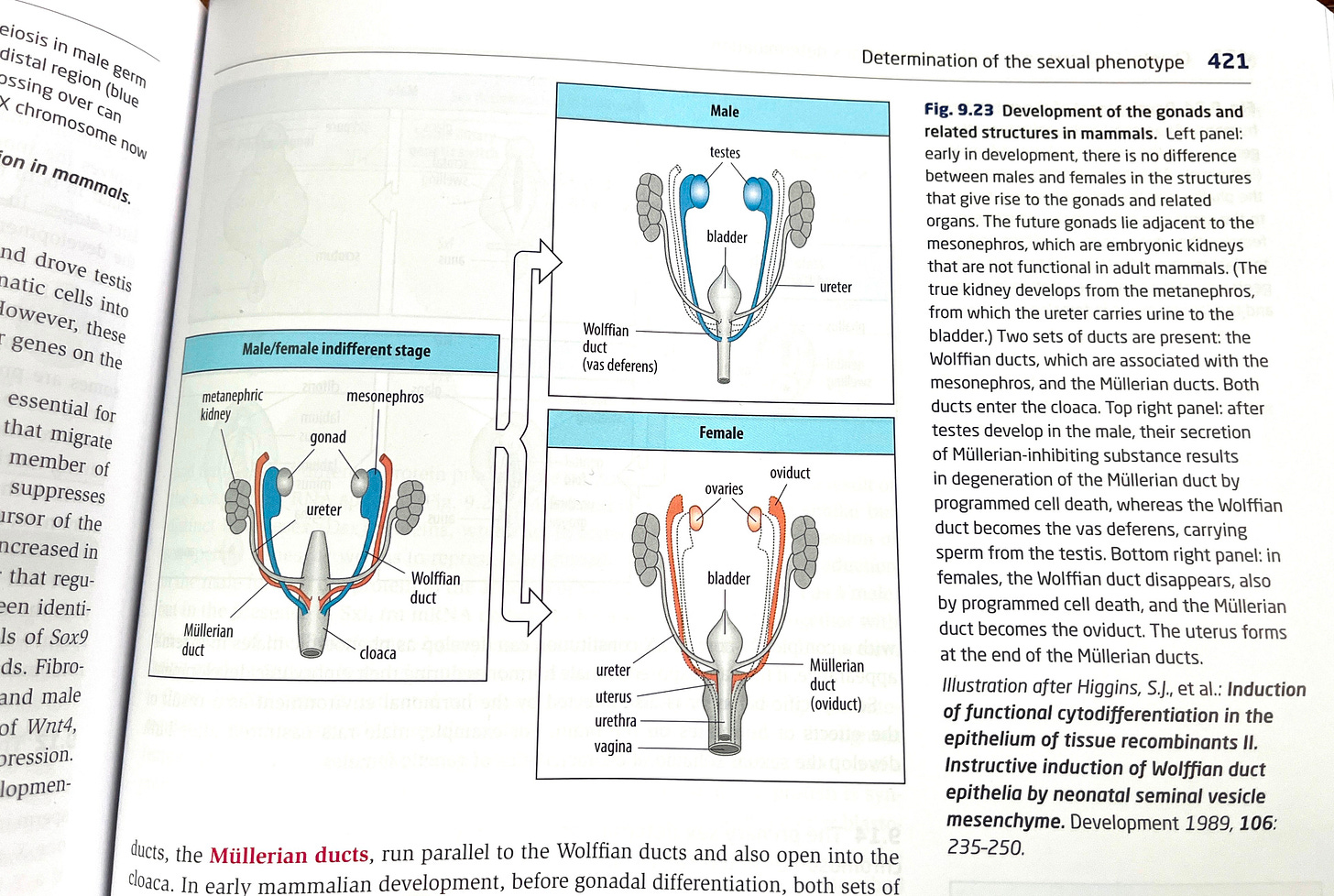

Further, male embryos don’t begin with ovaries and transform them into testes. Instead, every embryo starts with bipotential gonads—tissues that can become testes or ovaries depending on genetic signals. All embryos also share early Müllerian and Wolffian ducts and a common cloaca, none yet organized as male or female. This is not female anatomy; it’s the undifferentiated—or “indifferent”—stage, described clearly in modern developmental biology textbooks, such as the one below from Oxford, and various scientific papers.

From here, genes set at conception guide development for both sexes: XY embryos develop the bipotential gonads into testes, eliminate Müllerian ducts, and develop the Wolffian structures. XX embryos develop the bipotential gonads into ovaries, eliminate Wolffian ducts, and develop the Müllerian structures. In sum, both sexes start undifferentiated, develop their own sex-specific structures, and actively block the opposite sex pathway.

So, starting from an undifferentiated state does not mean we all start female. Saying otherwise is like claiming a block of unshaped marble is already a statue.

And if you want to test the myth, ask a simple question: Do male embryos begin with ovaries before transforming them into testes? They don’t—so the myth collapses.

So no—we don’t all begin female. We begin genetically sexed but physically undifferentiated, then develop along the male or female pathway determined by our genes.

For more on this, see our beautiful animation “Do We All Begin Female?” which walks you through the story of where the myth originated and what the science says.

Paradox Proofs is a new series where we debunk common biology myths or dive into interesting biology facts in under three minutes.

Scientific sources

Biason-Lauber, A. (2012). WNT4, RSPO1, and FOXL2 in sex development. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 30(5).

DiNapoli, L., Capel, B. (2008). SRY and the standoff in sex determination. Molecular Endocrinology, 22(1).

Eggers, S., Sinclair, A. (2012). Mammalian sex determination—insights from humans and mice. Chromosome Res, 20:215-238.

Gershoni, M., et al. (2017). The landscape of sex-differential transcriptome and its consequent action in human adults. BMC Biology, 15(7).

Kim, Y., Kobayashi, A., Sekido, R., et al. (2006). FGF9 and WNT4 act as antagonistic signals to regulate mammalian sex determination. PLoS Biology, 4(6).

Mullen, R., Behringer, R. (2015). Molecular genetics of Mullerian duct formation, regression, and differentiation. Sex Dev, 8(5), 281-296.

Ottolenghi, C., Pelosi, E., Tran. J., et al. (2007). Loss of WNT4 and FOXL2 leads to female-to-male sex reversal extending to germ cells. Human Molecular Genetics, 16(23), 2795-2804.

Prunskaite-Hyyryläinen, R., Skovorodkin, I., Xu, Q., et al. (2016). WNT4 coordinates directional cell migration and extension of the Müllerian duct essential for ontogenesis of the female reproductive tract. Human Molecular Genetics, 25(6).

Rey, R., Josso, N., Racine, C. (2020). Sexual differentiation. In: Endotext. South Dartmouth, MDText, Inc.

Warr, N., et al. (2012). The molecular and cellular basis of gonadal sex reversal in mice and humans. WIREs Dev Bio, 1.

Wilson, D., Bordoni, B. (2023). Embryology, Mullerian ducts (paramesonephric ducts). In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): Stat Pearls Publishing.

Wolpert, L., Tickle, C., & Martinez Arias, A. (2019). Principles of Development (6th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Zhao, F., Franco, H., Rodriguez, K., et al. (2017). Elimination of the male reproductive tract in the female embryo is actively promoted by COUP-TFII. Science, 357(6352), 717-720.

Zhao, F., Yao, H. (2019). A tale of two tracts: history, current advances, and future directions of research on sexual differentiation of reproductive tracts. Biology of Reproduction, 101(3).

Very informative read! I was also puzzled by this, but you explained it very nicely. I also tried to explain The Stone Paradox as my first article. Kindly review it once and share your thoughts and suggest improvements here:

https://substack.com/@superxwrites/note/p-182209084?r=72m1li

Thank you!

Great job, Zach! Thank you for your work and it is great to see you here!